Hens Lay Eggs

food for thought

Marketing or Profit?

The decision to participate as a vendor at any event for any business—and especially for authors and artists—depends on the vendor’s focus: marketing or profit. For many authors, the focus is marketing because it’s difficult, if not impossible, to earn sufficient revenue covering:

- Vendor registration fees

- Travel expenses (fuel, mileage, meals)

- Hotel accommodations

- Inventory

- Time.

Let’s plug in some general but realistic numbers:

- Vendor registration fees: For book/author-oriented events, author registration fees aren’t cheap. Most I’ve seen range from $150 to $350 per author, which includes one table and one or two chairs. So, I’ll split the difference on the lower side at $200.

- Travel expenses: At the current IRS reimbursement rate of 70¢ per mile, a round trip of 100 miles is worth $70. Let’s be kind to the author’s wallet and allow a per diem for meals at $25 per day.

- Hotel accommodations: Let’s be conservative and allot a base room rate of $100 per night for an economy chain hotel.

- Inventory: Depending on the number of books ordered, this varies. Regardless, even at wholesale, carrying sufficient inventory requires an outlay of funds. Let’s allot $7 per book for production and shipping and assume the author will bring 50 books. So, the author’s cost here is $350.

- Time: This is the big variable, because how much is your time worth? Even if an author or artist is generous with himself and calculates the value of his time at minimum wage ($7.25/hour federal), that still works out to $58 for an 8-hour day of working the table.

Here’s our total: $200 + $70 + $25 + $350 + $58 = $703.

If I’m selling books at an average price of $12 each, then I’d have to sell 60 books to break even. But if I only bring 50 books, then something’s got to give. Either the author absorbs that cost or the author shifts the focus of participation from profit to marketing.

The real value of event participation isn’t in the money an author makes; it’s in the marketing. An author who uses that time to interact with prospective readers and current readers establishes a personal connection with them. Building rapport is a huge aspect of effective marketing because people prefer to buy from people whom they like. This requires a degree of salesmanship and amiability that the typically introverted author may find uncomfortable.

I’m a diehard introvert, but early exposure and training in retail sales as a teenager forced me to learn how to smile and approach strangers with a friendly hello and to invite conversation with them. I’ve made a lot of sales simply because I enacted the first rule of marketing: acknowledge the prospective customer.

What I haven’t done and should do is to track my sales to see if there’s an uptick after an event. That’s one way to determine whether the marketing effort worked as intended.

Regardless, although I hope to recoup my expenses at every event, it doesn’t always happen. Actually, if I count the value of my time—and I value my time above federal minimum wage—then it never happens. Therefore, I adjust the variables. When my friend drives, I get to eliminate mileage costs from the total. I simply don’t factor in the value of my time. I sell merchandise other than books and hope my painting sell, too, to offset the costs. I don’t count the expense of tablecloths, tables, folding chairs, signage, business cards, and the other accoutrements necessary for a vendor’s stall.

Authors and artists put a lot of their personal resources and passion into producing books and art to share with the world. We deeply appreciate our customers’ support.

Yes, there will be a new book soon!

Buckle your seatbelts! The sixth and final book in the Twin Moons Saga is coming out this summer.

Titled Light of the Twin Moons, this story connects Iselde (a secondary character from Book #5: Champion of the Twin Moons) and Marog (the villain from Book #1: Daughter of the Twin Moons). Marog in this story no longer uses his original name but calls himself Koriolis.

Light of the Twin Moons breaks from some of the patterns set in the previous books in the series:

- The main male character’s name—not the female main character—begins with a “k” sound, and the name actually begins with a K. Earlier book protagonists were:

- Thelan and Catriona

- Falco and Calista

- Uberon and Corinne

- Ishjarta and Cassandra

- Chastian and Coral

- Koriolis and Iselde.

- Both protagonists are (or were) fae.

- The FMC is older and more powerful than the MMC. But let’s face it: when you’re dealing with immortals who are thousands or tens of thousands of years old, the age gap doesn’t really make any difference. They’re both ancient.

Some themes hold true, such as:

- There’s a strong arc of redemption in this story. Marog (aka Koriolis) was the reprehensible villain from the first book. He’s got a long way to go to redeem himself.

- The oracle gets involved, although this time she’s actively manipulating events to suit her purposes. (Let me tell you, Iselde doesn’t appreciate her other’s machinations.)

So, what happens in Light of the Twin Moons? I’m still working on the back cover copy, here’s the gist:

Fed up with her daughter’s defiance, the fae oracle sends Iselde to the mortal realm where she encounters the king of the New Orleans vampires, a fae-turned-demon named Koriolis. Unfortunately for her, she is his one true mate.

The iron of the moral realm infects Iselde. To resist the corruption, she accepts the mate bond, just as the oracle intended. However, mating is only a stop-gap measure; Iselde must return to the fae realm if she’s to survive without turning into a demon, too. The oracle offers them that opportunity, but first they must retrieve a legendary sword: Asi.

Finding Asi requires traveling to the Indian subcontinent. Their search takes them to a derelect temple in India where they meet the Indian god Indra who rather resents having been downgraded from the “maker and destroyer of worlds” to a mere rain god.

With Asi finally in their possession, the oracle returns Iselde and Koriolis to the fae realm and tosses them to the not-to-tender mercies of the midnight and dawn unicorns in the Deepwood. The unicorns lay a compulsion upon Koriolis, needing a demon to exterminate other demons. (Fight fire with fire!) The unicorns release them and they make their way to Djaria, the desert nation of djinns, the hereditary enemy of the fae.

Indra follows them to the fae realm; he wants to reestablish himself as both a mighty god and king. Koriolis and Iselde just want to be left alone, but he cannot resist the compulsion laid upon him. It gets bloody fast. And frequently. The relationship between Koriolis and Iselde deepens, and their trust in each other grows. Iselde asserts her free will and, with the help of the Unseelie King Uberon, manages to break the compulsion enslaving her mate. Koriolis does redeem himself through action, not through words. Iselde is no longer alone or lonely.

Yes, there’s an HEA.

Yes, I have a lot of work to do to turn that into an effective hook.

So, here’s the plan:

- Finish editing and revision by June 30.

- Revise and finish proofreading by July 15.

- Publish by July 31.

In the meantime, I’ve begun writing the fourth and final book of the Triune Alliance Brides series. This book will be the sequel to Triple Burn and conclude Ursula’s story with a bona fide HEA, not a bittersweet ending. Look for this book to come out by December 31.

Are we oversensitive?

“Gatekeeping” is typically a claim made by authors who resent being urged to hire professional editors, designers, and graphic artists to produce quality books. They view the reading public’s expectation of and demand for quality as prohibitive and unreasonable because they publish their books for themselves and want to acquire fame and fortune from those books.

I understand it. I used to be one of them.

However, there’s another kind of gatekeeping, and an entire branch of service has formed around it: sensivity reading.

Sensitivity reading stems from the conviction that authors are not able to and should not write characters if they don’t have the lived experience of those communities from which those characters are derived. To do so assumes adherence to pejorative stereotypes and incites outcries of cultural appropriation. The offended typically apply this to white authors writing Black characters.

I disagree.

In an age of political correctness, gender ideology, and heightened sensitivity to slights perceived and real, it’s easy to take offense and ascribe insult where none is intended. JP Sears illustrates this delightfully in his YouTube post here: “How to Get Offended.” (I also think no one has the right to not be offended. To live without being offended is not a reasonable expectation. One cannot go through life without giving offense or taking offense at something every so often.)

However, I offer examples as to why the false dictum that one must have lived experience in order to write a well-rounded, compelling character is, quite simply, wrong. For instance, no one alive has lived experience from the Revolutionary War or the Civil War. By the sensitivity reader’s claim, that means no one is able to write an authentic character from such a time period because that author hasn’t lived it. Historical fiction is a popular genre, so this alone debunks that concept.

I believe an author can and should write what he or she imagines and should also conduct the research necessary for versimilitude.

Tony Hillerman did that with his Navajo series. The protagonist is Joe Leaphorn, a tribal police chief. He lived in the time the stories take place (the 1970s), and he did the research necessary to deliver verisimilitude to readers. The series is popular, and I’ve not seen folks protesting against him or his books for cultural appropriation.

Of course, sometimes research isn’t feasible. A science fiction author who writes about blue-skinned, four-armed, reptilian aliens from some faraway planet in the universe cannot have that lived experience. Nor can an author who writes classic fantasy starring elves, dwarves, orcs, and other mythological creatures.

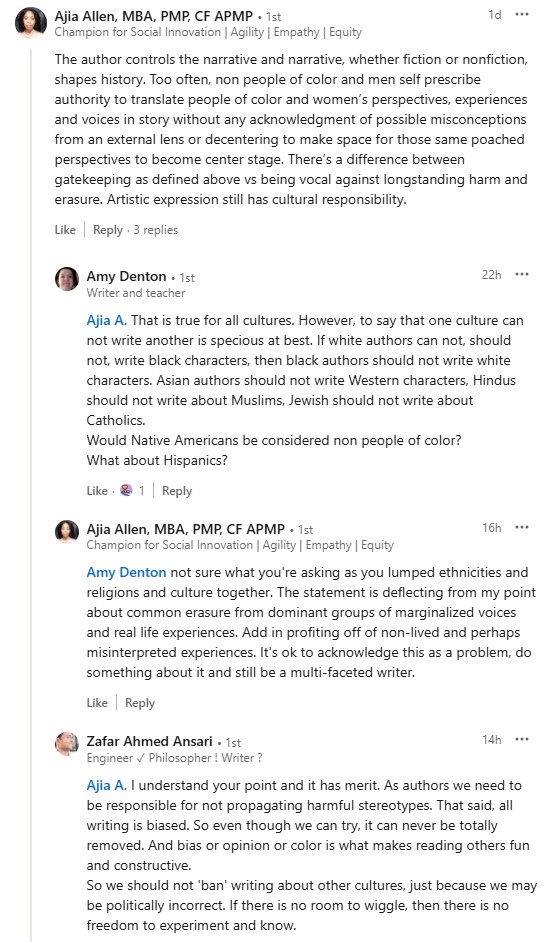

I posted on this topic in LinkedIn. The responses were gratifying:

Zafar Ahmed Ansari commented: “I agree. As per sensitivity reading I will never be able to write outside my culture. It will definitely be limiting. I think we should let the reader be the judge of that. If it feels off or unreal the reader will take care of it.”

And Lindsey Russell quipped: “Totally agree – what ‘life experience’ of murdering dozens of people did Agatha Christie have?”

So, how many people did Agatha Christie murder or how many murders did she solve to enable her to write stories about Miss Marple and Hercule Poirot? My guess is none, yet she’s been an all-time best-selling author for nearly a century.

In a recent argument on an FB community, I pointed out the fallacy of lived experience being required to write fiction by using similar examples and was accused of drama. I don’t think I was being dramatic, but I do think the person who disagreed so strongly with me was being dogmatic and a gatekeeper. So, let me repeat this: Write what you can imagine and do the necessary research for verisimilitude. So, no, the author doesn’t need that lived experience, although sometimes research does involve—and is enhanced by—lived experience.

If we may only write from lived experience, then our stories would be limited and the scope of our stories small.

Author

Hard boiled, scrambled, over easy, and sunny side up: eggs are the musings of Holly Bargo, the pseudonym for the author.

Follow

Karen (Holly)

Blog Swaps

Looking for a place to swap blogs? Holly Bargo at Hen House Publishing is happy to reciprocate Blog Swaps in 2019.

For more information: